Jules Bourbeau ’25

Arts Editor

Only a handful of the “conlangs” ever created have breached the sphere of their creators and close acquaintances, including Tolkien’s Quenya (one of the Elvish languages), Dothraki from Game of Thrones, and Mando’a from the Star Wars universe. “Conlang” is a portmanteau of the words “constructed language,” and the art of creating one is called “conlanging.” There are three main types of conlangs: “engelangs” (“engineered languages”) are designed to meet some particular goal or communication type, “auxlangs” (“auxiliary languages”) serve to facilitate communication between multiple different existing languages, and “artlangs” (“art languages”) are usually intended for use in a fictional setting, but also include conlangs that might exist solely for the sake of a joke.

Creating a custom language requires an intimate knowledge of several different branches of linguistics, including phonology and phonetics, morphology, syntax, and more, depending on the project’s goals. As for myself, I have only a modest proficiency in linguistics, but I will use the example of my own conlang creation to highlight the joys and difficulties of this underrated hobby.

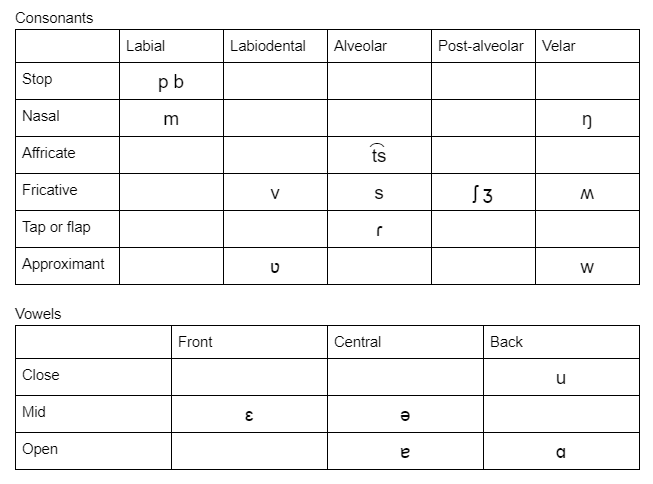

My language is an artlang called “Tsau” designed for a fictional species of horse-like humanoids living on the northeast coast of a supercontinent. It originated as a COVID project but is still very much a work in progress. I began the process with choosing the various phonemes, or sounds, I wanted in my language. This required an understanding of the IPA, or the international phonetic alphabet, which gives a unique symbol to every sound in all the world’s languages. The consonants and vowels that show up in a language are essentially arbitrary, meaning that I could choose more or less entirely based on which ones I thought would sound interesting.

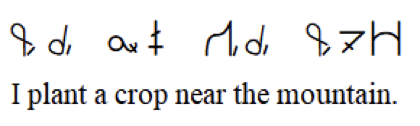

Next, I pivoted to developing the orthography, which is a language’s writing system. I wanted to work with a syllabic orthography, one in which each grapheme (character) represents one syllable, with a few exceptions. In Tsau, each consonant has one base symbol, with an additional feature, such as a dash or underline, representing the vowel following it. A handful of vowels and consonants can also stand alone as their own grapheme, hence the exceptions. This was heavily inspired by Japanese hiragana and katakana, which work somewhat similarly.

I then turned to Latin for how to structure the grammar of my conlang. I chose a case system for the nouns with six cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative to, dative for, and instrumental. Then, also like Latin, each noun has a declension, of which there are five based on the phoneme that the noun ends with. I also largely based the verb system on Latin but stuck to only two different declensions.

Other than creating a handful of words to fill the dictionary, I have largely stopped here for now. There is still an immense amount of development needed to make Tsau into a fully-fledged language, such as pronouns, tense, and likely a whole slew of features that I do not have enough experience to even know about. Needless to say, a lot of work goes into making a language. No doubt, plenty of long-time conlangers would have a field day absolutely tearing apart Tsau. Do not let that discourage you from creating your own language, however. Ultimately, you should approach conlanging, like any hobby, as something to be enjoyed, and if you follow processes similar to my own, you will no doubt learn a lot about linguistics along the way.

+ There are no comments

Add yours